We're Leaving TikTok - And We're Calling on Other Outdoor Brands To Do The Same

If I’m being honest, I never wanted to be on TikTok in the first place. My business, Timpanogos Hiking Co., was inspired by a desire to leave the screen-saturated, alienating excesses of the COVID pandemic behind and reconnect with real things — like mountains and rivers and canyons.

Our motto at Timpanogos: “escape the noise.”

TikTok was literally the noise.

But it was a necessary evil, I rationalized. Patagonia was there. North Face was there. We had to meet people — especially young people — where they were.

And a lot of young people are on TikTok. An estimated 120 million Americans, to be exact, at least 60% of whom are under the age of 30. Among teenagers, it’s even more widely used. At least 63% of 13–17 year olds are on TikTok. Many of those young people report using the app at least 2–3 hours a day. Some say they use it near-constantly when they are not in classes.

Needless to say, it’s probably not a great business decision to leave such a massive, influential platform.

We’re doing it anyway.

Here’s why.

I’m from the in-between-generation sometimes referred to as Xennials–part Gen-X, part Millennial. It’s an era captured very well in the Netflix show Stranger Things. I grew up on The Oregon Trail, Spielberg, Star Wars, and a freedom unimaginable to kids today.

For those of us from this era, however, it’s also given us a unique vantage point in history. Not only did we straddle different millennia (I graduated from high school in 1999), we have experienced essentially two different realities: the end of the Analog Age and the dawn of the Digital Age.

My childhood was populated with exciting new technologies — Walkmans and Discmans, Nintendos and Gameboys, computers, the internet…

But still, life didn’t revolve around any of these technologies. I spent a lot of time outside, riding bikes, playing basketball, hanging out with friends, all without the incessant urge to check a device. Smartphones didn’t arrive until the late 2000s. By that time, I was an adult in my late 20s. My brain (in theory) was fully developed.

And it was the smartphone, even more than the Internet, that turned out to be the big game changer.

Bestselling author and social psychologist Jonathan Haidt refers to the years the smartphone became fully adopted, 2010–2015, as “the great rewiring.” It not only changed the culture, it literally changed our brains. Especially for kids.

There have been concerns, of course, about all popular new technologies going back to the printing press. In my generation it was video games and MTV. In previous eras it was television or rock and roll or jazz. Usually these fears about “ the new thing” are over-amplified and the actual consequences exaggerated.

Smart phones, though, seem to be different and here’s why.

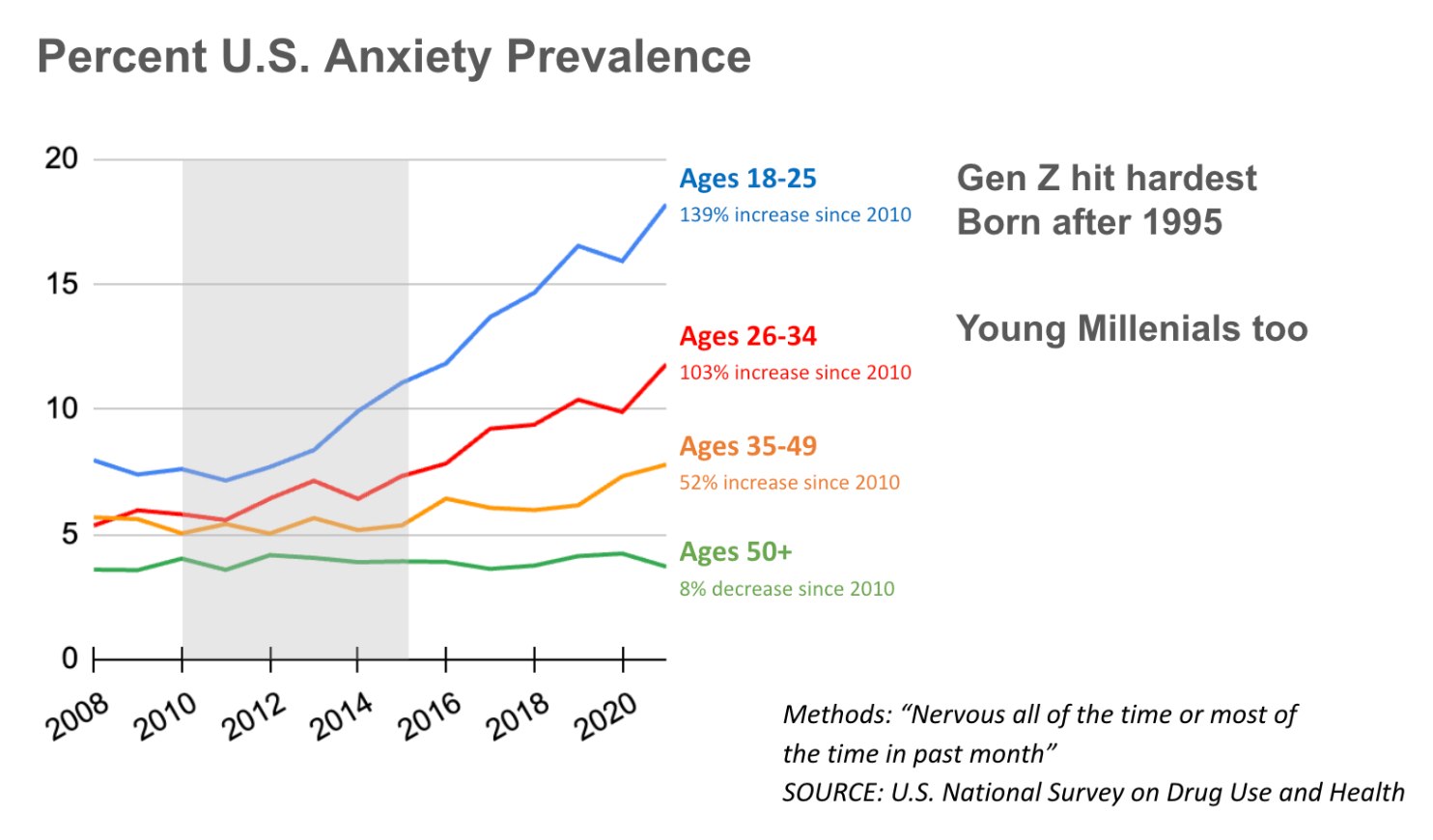

There is a precise correlation between an unprecedented decline in mental health and the arrival of the smartphone. As Haidt describes: “Rates of depression and anxiety in the United States — fairly stable in the 2000s — rose by more than 50 percent in many studies from 2010 to 2019. The suicide rate rose 48 percent for adolescents ages 10 to 19. For girls ages 10 to 14, it rose 131 percent.”

This dramatic mental health decline is different from any technology that preceded it.

That decline, as shown in the chart above, has been particularly bad for the cohort known as Gen Z (those born in the late 90s/early 2000s). And even more pronounced among teenage girls.

I’m not advocating ditching smartphones altogether. I use mine to run my business (among other important things). It’s the apps we put on our phones that largely determine their effect. Some are designed to be functional. Some are designed to be creative or communal. And some are designed for addiction.

Owned by Chinese corporation ByteDance, TikTok officially hit the scene in 2016. By 2018, the app had already been downloaded by over 100 million users. It officially dethroned Instagram as the most popular social media platform for young people in 2023.

From the get-go, the platform has been a lightning rod for a number of issues, from mental health to data collection to political extortion to algorithmic manipulation. In 2023, the state of Utah, where my business is based, filed a lawsuit against the company for “intentionally causing harm toward Utah’s youth.”

More recently, national headlines have swirled over a potential ban of the platform in the United States due to national security risks. The company’s fate is currently being reviewed by the Supreme Court. President-elect Donald Trump meanwhile is reportedly looking into a potential political resolution with the company.

No one app is responsible for the mental health epidemic, of course. But TikTok is, by design, uniquely good at, well, making our mental health bad.

Part of this has to do with the content. In a highly-cited piece, “Driven into Darkness,” Amnesty International found that TikTok’s “For You” feed actively glorified trauma, self-harm, and suicidal ideation. Beyond such extremes, it’s slot-machine-like content favors viral “trends,” sensationalism, and cheap dopamine hits. These features have been part of the media and entertainment playbook for decades — just never before in such a sophisticated, manipulative, addictive algorithm. That algorithm keeps people, young people in particular, glued to their screens for hours on end.

The irony is that it doesn’t feel this way when you’re using it. It often feels great, at least at first. USC professor and author Dr. Julie Albright describes it as “digital crack cocaine.” The algorithm finds what you like and shows you an endless flow of it (mixed with some sometimes disturbing guidance). “You’ll just be in this pleasurable dopamine state, carried away,” Albright says. “It’s almost hypnotic, you’ll keep watching and watching…”

To be clear, there are a lot of great content creators, and content, on the platform. Some promote very healthy activities, including getting outdoors. I’ve spoken to a number of people I respect who remain on the platform for reasons I understand.

But the net effect for most users, especially young people, is clear. It increases isolation, anxiety, and depression.

I have no idea how the potential “TikTok ban” will play out in the coming weeks and month. My best guess, given the amount of money involved, is that some resolution will be reached.

But the decision for my brand comes down to this:

We’ve got to do right by the rising generation. We’ve got to stop giving them drugs and shrugging or pointing fingers at them when the obvious outcomes arrive.

On average, US teenagers spend nearly two hours on TikTok each day. It’s having a clear detrimental impact on their attention span, social life, and overall health.

At Timpanogos Hiking Co., we’re done contributing to these stats. We are confident young people will be much happier and healthier doing other things, ideally, physical things that have the potential to rewire their brains and strengthen their mental and physical health in powerful ways.

I’ve personally been inspired by purpose-driven brands like REI, Patagonia, and Cotopaxi that stand for things. They made me believe that businesses could be about more than just profits.

We’re much newer and smaller as a brand but we’re throwing a challenge back their way.

Do the right thing. Join us. Leave TikTok.

The real world is calling and we must go.

Well said, and very well done! I hope the other companies will choose to join you, but at the very least you can be happy in knowing you are doing what you feel is right and living up to your motto. Thank you!

I had purchased a few of your shirts because I liked them. I’ll buy more now because your words. Thank you.

Great piece, Joe. You are truly making a difference for the good. I love the purpose behind your brand and I will always support and be a fan of Timpanogos Hiking Co.

There are limited ways to fight this “free” market. Another platform will inevitably fill the TikToc space. Regardless we must all stick to our purpose. Always be true to yourself.

I love this, thank you so much for this example!

Leave a comment